Matters Psychological and Theoretical in the Second Piano Sonata, opus 40 (1975) by Hubert du Plessis

In this month’s blog post, Dominic Daula explores Hubert du Plessis’ Second Piano Sonata. Dominic completed undergraduate and postgraduate studies in music at the University of Cape Town under the tutelage of James May and Franklin Larey. He currently studies the piano with Richard Ormrod at the Royal Northern College of Music as a Pidem scholar.

Hubert du Plessis (1922 – 2011) is the second in a significant triumvirate1 of Western Classical composers to have emerged from South Africa in the first half of the twentieth century. He grew up on a farm in the Cape Province, and in 1943 he obtained a Bachelor of Arts in Music and English from Stellenbosch University. As a composer, he was mentored by W. H. Bell, Friedrich Hartmann, and Alan Bush. Du Plessis’ career as a musician was multi-faceted: as an academic, he accepted a Lectureship at the University of Cape Town (1955 – 58) and later, a Senior Lectureship at Stellenbosch (1958 – 82). During this period, he published the first biography of J. S. Bach to be written in Afrikaans (1960), as well as an edition of his correspondence with W. H. Bell (1973). He was a prolific recitalist, particularly on the SABC (South African Broadcasting Corporation). As a pianist, he specialised in the works of Liszt and Scriabin; and as a harpsichordist, his repertory included Bach’s Goldberg Variations and the Pieces de clavecin by François Couperin.

Du Plessis had some standing as a so-called ‘establishment’ composer. Indeed, some of his major works were commissioned for national occasions, including Suid-Afrika: Nag en Daeraad (1966),2 considered by some as his most patriotic work3 and written during a period in which the composer was a supporter of the Nationalist government, 4 notorious for its policy of separate development (commonly known as Apartheid).

The year 1974 stands as one of significance in du Plessis’ life and career. In the preface to his Second Piano Sonata, the composer describes how he underwent a ‘harrowing personal experience’5 which led him to suffer ‘mental and physical illness’.6 The composer never shared in great detail what triggered his misfortune, though it was suspected by colleagues that the complicated circumstances of his romantic relationship at the time stood as contributing factors.7 Given his reportedly erratic and professionally questionable behaviour, the Rector8 of the University granted du Plessis sick and study leave until the second quarter of 1975.9

During the course of his sabbatical, du Plessis proved to be incredibly prolific: as a pedagogue, he birthed a major treatise titled The Maintenance of Keyboard Technique; and with regard to composition, he completed three works – namely the Second Sonata, the Requiem aeternam (opus 39) for choir, and (as an extension of his pedagogical focus at the time) the Ten Piano Pieces for children and young people (opus 41). With the exception of the Ten Piano Pieces, du Plessis fashioned an autobiographical narrative onto the compositions of this period. The Second Piano Sonata, according to du Plessis, chronicles the entirety of his personal crisis,10 and the Requiem aeternam stands as a bespoke piece to be performed at his own (hypothetical) cremation – though he is quick to add that the work was not written with sentiments of morbidity.11

The Second Sonata was written in response to a commission from Samro12 and differs greatly from the First,13 which stands as a purely abstract composition. The personal ‘states of mind’ that the composer portrays in this work are that of ‘captivity’, ‘insanity’, and ‘liberty’: these form the titles of the respective movements. According to his notes, the composer wrote Insanity first, and a great deal of it in one sitting—du Plessis goes as far as to say that he had been in a state of delirium during this process.14

As regards the other movements, the order of their composition is not discussed in the sources that are available in the public domain. The Insanity movement, as the first to be composed of the three, forms the psychological and theoretical basis of the Sonata. In the course of this movement, the composer introduces an aspect of tonal symbolism, where he deliberately makes use of D major and E-flat minor (the principal tonalities throughout the second and third movement) as representative of life and death respectively.’15 This aspect of tonal symbolism may be applied to an autobiographical narrative: that of a composer’s life potentially hanging in the balance in the face of their difficulties.

What is more, du Plessis forges a link between the Sonata and Alexander Scriabin, to whose memory this composition is dedicated. The Scriabinesque links are not to be found in brevity alone;16 the work also means to observe the centenary of his birth.17

Du Plessis unpacks the link to Scriabin even further, stating that:

The titles of my Sonata movements are applicable to his clearly demarcated third period: the captivity caused by his grandiose ideas and his use of devised chordal structures as a basis for compositions virtually led to insanity, from which he was granted liberty by his merciful death at a comparatively early age.18

The following section will upack certain aspects of structural unity in the Sonata that I discovered through my practical study of the piece. The first aspect to be discussed will refer to pitch organisation (stated thematically and harmonically) and the second will unpack quintical groupings, first exposed through attack, and developed through rhythmic means.

1. Hexachordal aspects

In his programme notes, du Plessis reveals how Captivity may be reminiscent of a Fantasia, given its sectional design.19 Though the movement lacks the contrapuntal rigour typical of fantasias proper to the earlier repertory, I have discovered that Captivity makes use of a hexachord as a central aspect of its thematic content. The use of a hexachord as the basic cell of a fantasia dates back to the stile antico, where composers would display their contrapuntal skills through the presentation of hexachords in different permutations for the duration of a composition. Those that fall within the gamut are considered hard (starting on G), soft (starting on F) and natural (starting on C), and full hexachordal entries commencing on notes other than the three mentioned are generally classified as fictive, with minor exceptions.

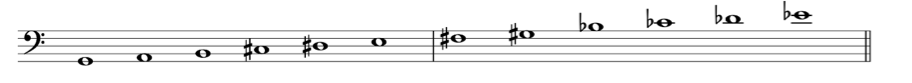

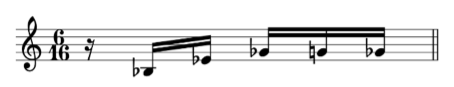

In Captivity, du Plessis adapts these theoretical strictures to a more harmonically fluid idiom and exposes two successive hexachords in the first division of the movement. The musical example below illustrates the hexachords alone, that is to say without any other textual information in the Sonata proper. As can be observed, they do not fit into the classical perception of hexachords proper to the musica recta.

Note that the first hexachord gives the impression of it starting on the durum (that is, on G), though this is not completely realised as the distance between the third and fourth degree is expanded to a whole tone as opposed to the typical semitonal interval. The second hexachord begins on a pitch not proper to those mentioned before. Furthermore, the interval between the third and fourth degree is a semitone and thus it may be classified as fictive, despite the composer’s dubious spelling in this hexachordal series.

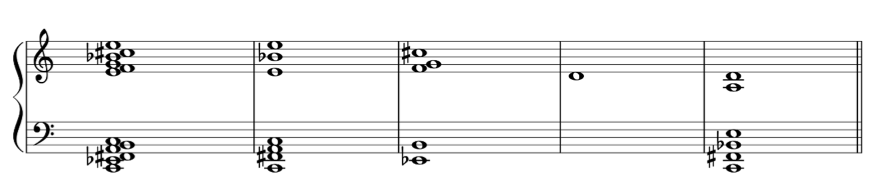

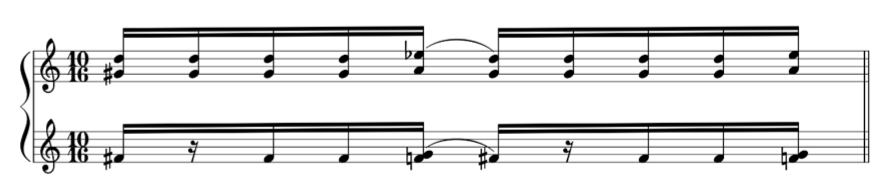

As an extension of the link to Scriabin, the composer makes reference to the mystic chord in the Insanity movement, where he presents two sets of hexachords as harmonic statements in both hands. This is the most dissonant part of the entire Sonata and stands as its compositional apex.

To unpack example 2, it should be mentioned that the two hexachords stated harmonically in ‘bar 1’ should be considered as a single compound. This harmonic compound (rooted on C) should be compared to Scriabin’s mystic chord (placed in ‘bar 5’ of this example). The mystic chord shares the same root as du Plessis’ harmonic compound.

The harmonic compound in ‘bar 1’ qualifies as a quasi-mystic chord in principle, due to the fact that it shares a number of mutual pitch relationships with Scriabin’s – including similar quartal attributes – though it must be mentioned that the compound also contains pitches foreign to the mystic chord rooted on C. ‘Bar 2’ isolates the pitch classes in du Plessis’ harmonic compound that are shared with the mystic chord proper (‘bar 5’). Therefore, ‘bar 2’ may be considered as the quasi-mystic chord (without the foreign pitches of the harmonic compound in ‘bar 1’). ‘Bar 3’ is a collection of residual pitches belonging to the harmonic compound exposed in ‘bar 1’. These are foreign to the mystic chord rooted on C. However, special attention should be paid to its overwhelmingly tritonic character, which can be rooted in du Plessis’ understanding of the mystic chord’s structural content. ‘Bar 4’ highlights the pitch class omitted from the quasi-mystic chord that would otherwise result in du Plessis’ compound in ‘bar 2’ as analogous (at least in principle) with the mystic chord rooted on C.

2. Quintical considerations

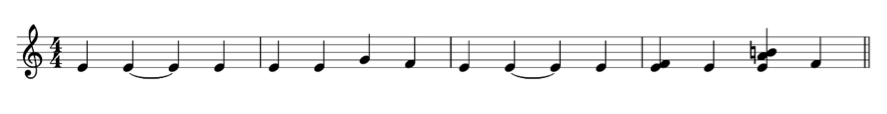

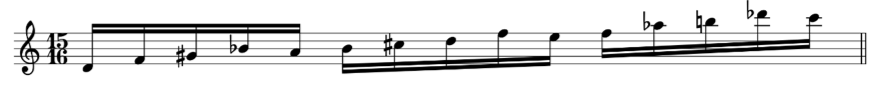

Another aspect of interest is the organisation of motivic material into groups of five, either from a rhythmic standpoint or by attack (that is, the number of times a note is struck). The earliest quintic aspect that the composer devised would be the opening motif of the Insanity movement, which ruminates around the note E. As depicted in example 3 below, significant leaps in the motif occur after the note has been struck for the fifth time. The word ‘struck’ has been chosen with great care, and the reader should be made aware of the tied notes within the motivic statement.

Copyright © 1992 by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

A second major example may be located in Captivity, where the motivic refrain (which the composer considers as ‘important’)20 should be considered as related to the opening material of Insanity, not least in its pitch repetitions (a phenomenon that occurs in both motifs), but also for its rhythmic organisation: the motif itself spans for the duration of five crotchets. The crotchet rest, therefore, should be discounted in this instance.

Copyright © 1992 by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

As can be deduced from my terminology, the function of this particular motif is similar to that of a refrain, meaning that it appears before and after each episode in the movement. Note that the pitch last to be repeated in the motivic refrain is quitted by step, as opposed Ex. 3 where the last note to be repeated in the motif is quitted by leap.

Liberty, the third movement, develops the material of Insanity and Captivity. In the first instance, a rhythmic diminution of the motivic refrain in Captivity forms the introductory motif of Liberty. This diminution is not applied systematically: the material in Ex. 4 consists of crotchets and quavers, whilst Ex. 5 contains semiquavers only. However, rhythmic organisation remains a common point between the two motifs, for both span over five crotchets and semiquavers respectively, and are preceded by a rest of one beat of the common note value per example.

Copyright © 1992 by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

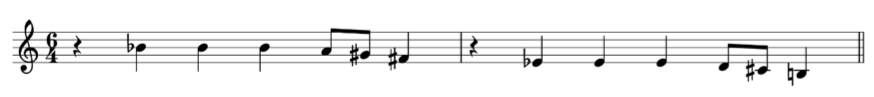

The opening of the rondo section in Liberty organises the material in a more systematic quintical grouping, as evidenced by the time signatures in Ex. 6 and 7 – both being factors of five. Furthermore, the pitch repetitions first stated in Insanity return in Ex. 7 as dyads with a syncopated figure as its counterpoint.

Copyright © 1992 by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

Copyright © 1992 by the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

Epilogue

This Sonata has proved elusive to the South African public, evidenced by its lack of representation in commercial recordings.21 In October 2018, I included the work as part of a recital for NewMusicSA, the South African branch of the International Society for Contemporary Music. Though the Sonata can hardly be classified as ‘contemporary’ by date, it was certainly considered as ‘new music’ by the audience, given that many had never heard the work before. Furthermore, the Sonata’s compositional circumstances may not appeal to some performers, especially those who feel that music exists purely as an abstract art and are sceptical of programmatic compositions. It is my opinion, however, that the Sonata stands as a significant autobiographical document that processes du Plessis’ anguish through a medium most familiar and natural to him. This, as well as its connection to Scriabin, opens the work to a number of programmatic avenues for recitalists and curators who wish to explore themes of cross-cultural connections, as well as expositions on artistic responses to setbacks in one’s mental health.

Endnotes

1 The others in this generation being Arnold van Wyk (1916-1983) and Stefans Grové (1922-2014). The notion that these men stand as a representative sample of South African Western Classical music of the twentieth century is being challenged. Certainly, their race, gender, and cultural background as Afrikaners has in the first instance elevated their positions as arguably the most documented composers to have emerged from South Africa in the past century. This observation does not take into account the quality of their output, of which some may discover to be extremely fine. One should take heed of the fact that some other composers of the pre-democratic era may have had fewer opportunities for career success and documentary outlets for posterity. Those affected include women, those of colour, as well as the non-Afrikaans.

2 The work is also known in English as South Africa – Night and Dawn.

3 Stephanus Muller, “Queer Alliances,” in Gender and Sexuality in South African Music, eds. Chris Walton and Stephanus Muller (Stellenbosch: SUN ePress, 2005), 41.

4 James May, “Obituary – Hubert du Plessis,” Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa 8:1 (2011), 116.

5 Hubert du Plessis, “Composer’s Note,” in SAMRO Scores: Hubert du Plessis – Four Piano Pieces, Op. 1; Four Piano Pieces, Op. 28; Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 40, Hubert du Plessis (Johannesburg: Samro, 1992), 34.

6 Du Plessis, “Composer’s Note,” 34.

7 Arnold van Wyk, letter to James May (19 December 1974).

8 Jan Naudé de Villiers was the Rector of Stellenbosch University from 1970 till 1979. ‘Rector’ is the term commonly used when referring to the Principal of an historically Afrikaans-medium university in South Africa, whilst ‘Vice-chancellor’ and/or ‘Principal’ are the terms used in the English universities across the country.

9 Arnold van Wyk, letter to James May (19 December 1974).

10 Edward Aitchison, “Hubert du Plessis,” in Composers in South Africa today, ed. Peter Klatzow (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1987), 64.

11 Hubert du Plessis, personal note to Edward Aitchison. Quoted in Aitchison, “Hubert du Plessis,” 50.

12 Established in 1961 as SAFCA; renamed in 1974 as the Southern African Music Rights Organisation.

13 First Piano Sonata, opus 8 (1952), premiered by the composer at the London School of Economics, 24 October 1952. An early review by William Glock remarked ‘… this is true piano music … [his] career[s] will be followed with close interest’, (The Scotsman, 22 December 1952).

14 Aitchison, “Hubert du Plessis,” 66.

15 Du Plessis, “Composer’s Note”, 34.

16 Du Plessis’ sonata runs for thirteen minutes.

17 This occurred in 1972.

18 Quoted in Aitchison, “Du Plessis,” 65.

19 Du Plessis, 34.

20 Aitchison, 65.

21 The sonata was broadcast on the SABC by Sini van den Brom in November 1989; a recording of that broadcast has been sought by the author from the public broadcaster for research purposes.