In this month’s blog post, Philip Robinson offers an assessment of current trends on the role of music in education, from school level up to higher education. Philip Robinson is a PhD student at Manchester University, researching transnational opera and festival-making in the Soviet Union during the 1930s. He also works as a peripatetic music teacher in schools and is Student Representative for the Royal Musical Association.

The startling decline of music in the UK education system has been well documented in the mainstream press, especially in the last year. The number of students applying to study GCSE music, for instance, has steadily declined from 8% in 2008 to a mere 5.5% last year, with fewer students taking on the subject at A-Level. The most commonly attributed cause of the decline rests on chronic underfunding in recent years, and low incentives for UK schools to support music on the curriculum.

On the latter, the introduction of the English Baccalaureate is particularly problematic. Introduced in 2010 as a means of judging school performance and rendering more rigorous the perceived ‘dumbing down’ of GCSEs. The system judges a school’s performance based on students’ attainment in English, maths, the sciences, geography, history, and modern foreign languages; the arts are entirely excluded. In light of this, the EBacc acts as a direct incentive for schools to minimize the role of arts subjects on the curriculum, and at a time where funding in education is scarce, the arts are invariably the first to go.

The fate of instrumental teaching is also gloomy. It was recently reported that the borough of Wrexham in North Wales has just cut funding to its scheme that offers subsidies for children to learn an instrument in schools by 72%, all in a bid to meet their savings targets. There are now fewer than seven Welsh authorities that fund organizations of peripatetic music teachers. County music services, state-funded organizations in the UK that employ instrumental teachers in schools, are now largely extinct. My local service in Cambridgeshire closed as I was doing my GCSEs ten years ago. Aside from the role such organizations played in supporting the education system, their dissolving has made peripatetic teaching an unstable career. My peripatetic teaching work relies on zero-hours contracts with no holiday pay, sick pay, or pension. Okay for helping me support my part-time PhD, but its a dispiriting environment in which to make a career.

Aside from staff shortage, the more troubling effect of this trend is that music education is in danger of becoming the property of those who can afford it. This was made particularly clear when it was widely reported that one school in West Yorkshire was charging students £5 at week for mandatory supplementary theory lessons to do GCSE music. GCSE music also usually necessitates the learning of an instrument. Unsubsidised, this could represent costs of well over £400 a year, an unattainable sum for many families. The problem is further demonstrated by the fact that as of last year The Royal Academy of Music remains the UK institution with the lowest number of students educated at state schools at 48.5%, ten percent lower even than Oxbridge. The principals of The College of Music and Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Colin Lawson and Julian Lloyd Webber respectively, have both blamed this on poor music provisions in schools.[1]

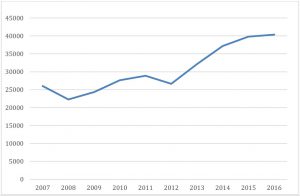

Yet despite the long-standing cuts to music on the school curriculum, it seems at least that people have not been dissuaded from studying music at university. Such statistics are hard to come by, and to find the numbers I ended up trawling through the many tables of raw data on the UCAS website. Applications to music courses have risen from around 25,000 in 2007 to over 40,000 in 2016, with the steepest rise beginning in 2012. The growth is promising, but it is unclear how this growth relates to the greater number of applications to university in general, or the proportion of applications coming from overseas students. Such information would take more detailed data, and a more competent statistician than me.

Table 1 – Applications to study music at university by year.

Source: https://www.ucas.com/files/2016-applications-detailed-subject-group

There is no shortage of evidence that music holds a valuable place on the curriculum. Music is a rich subject in and of itself, but its benefits extend beyond those who wish to make it their career. A longitudinal study published last month found that ‘test scores on inhibition, planning and verbal intelligence increased significantly’ for primary school children who benefitted from music lessons.[2] This study is one more contribution to the enormous body of evidence that demonstrates that exposure to music in schools improves academic attainment across the board.

The number of public figures who have defended the position of music in education is reassuring; they lie on a spectrum from Plato to Beyoncé. The decline of music in schools is little less than a crisis, and there has been no shortage of esteemed figures who have called it as such. But despite the vast body of evidence in support of the positive role of music education in schools, and the huge amount of high-profile and high-quality public advocacy, progress has been slow. If there is one thing that this has taught us, it is that there is no such thing as too much advocacy.

[1]https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/classical/news/julian-lloyd-webber-slams-plans-to-spend-millions-on-london-concert-hall-a6716421.html; https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/mar/14/royal-college-of-music-head-criticises-state-of-school-music-provision-budget-cuts.

[2] Artur C. Jaschke, Henkjan Honing, and Erik J. A. Scherder, ‘Longtitudinal Analysis of Music Education on Executive Functions in Primary School Children’, Frontiers in Neuroscience 12 (2018).

Bibliography

Aside from sources cited in the text, statistics in this article were taken from a number of articles, a selection of which may be found below.

‘The quiet decline of music in British schools’, The Economist, 1 March 2018,

‘Royal College of Music head criticises decline in provision in schools’, The Guardian, 14 March 2018.

‘Alison Balsom: “We have a music crisis in schools. Everyone needs to speak out’”, The Times, 16 March 2018.

‘Cambridge intake no longer most privately educated’, BBC News, 2 February 2017.

This is something which is showing like the tip of an iceberg. Music is used as a language (possibly more than it is for anything else), and is as common as air. I understand that mimicry is important in that communication, and so is propaganda through words in songs. The imagery and emotions people experience when watching a film for example, which has a soundtrack as loud as any speech in it, those images and feelings are remembered in the music playing at that time. When people next hear that music anywhere, those feelings are brought back. A simple reason for doing this is to cover a weak plot with stronger feeling. But the reason for saying this, is that if something is as common as air, why is it being less and less taught?

There are people who say ‘the language of music cannot be understood, it is on too deep a level’. This is not true, composers understand the building blocks of language they are using. Of course music is sometimes purely artistic. As a language, it is evolving, but there is none of it which is not understood. It involves mimicry of natural sound, man made sound, and conditioned sounds. But I am only a layman in this. My strong interest is in survival. For ten years I listened to nothing but BBC Radio 3, and in 2017 my poetry had reached a peak and was used in a 50th anniversary book to inspire the baby boomers. I’m 50 next year.

The gaping hole in understanding of music must be filled and properly. We would bring much more colour into the world if we allow things to continue as they are.