By Johanna-Pauline Thöne

Shortly after His Holiness Benedict XVI, Pope Emeritus, died on December 31, 2022, the voices of clerical conservatives became louder, criticising the reform agenda of Benedict’s successor, the current pope Francis. In early January 2023, the controversy culminated in the publication of the late pope Benedict’s memoirs by his private secretary, Georg Gänswein: from beyond the grave, Benedict now joined the debate to criticise his successor harshly. In an official statement, Pope Francis, in turn, emphasised the mutually consultative and respectful relationship between himself and the late pontiff, declaring that ‘his death has been instrumentalized by people who want to bring water to their own mill’.

In the late fourteenth century, by contrast, critique against the papacy was often voiced in a––to us––much more enigmatic manner:

‘This is the ultimate beast, of terrible sight, which will pull down the stars. Then the birds and creepers will flee, and nothing will remain. O terrible beast, you who devours all, hell awaits you. You are terrible, who will resist you?’

The original Latin text of this prophecy is accompanied by the depiction of a hybrid monster, the fera ultima, that signifies the end of time. As part of a larger series of apocalyptic prophecies, this text was recopied throughout the fourteenth century, and accordingly well-known at the courts of Europe. From the beginning of his pontificate in 1378, it carried the name Urban VI, referring to the Roman pope as the papal Antichrist. But how did it come to this?

These two vivid anecdotes about the papacy both raise questions about the mechanisms behind propaganda and its reception in society: who instrumentalised whom and to what end? Whereas in present-day debates, one can at least hear the opposed parties and analyse the reaction of the public, the conflicts of the Middle Ages are preserved only in written traces that happen to survive. Among these written traces, music is an important piece of the puzzle by which to evaluate the influences and impact of political propaganda on society––one which is often overlooked by historians. I exemplify this claim here through two case studies, which unveil interrelations between late fourteenth-century papal polyphony and late-medieval prophetic writings. As we shall see, the fera ultima of the Apocalypse is omnipresent.

The papacy was one of the major players in what can generally be described as a time of crises. Between 1347 and 1351, the black death had killed around thirty percent of the European population. England and France were involved in a series of military conflicts, known as the ‘Hundred Years War.’ Finally, from 1378 onwards, Christendom was divided between two competing popes, one in Rome and one in Avignon. This state of affairs––called the Great Western Schism––became even further entrenched with the election of a third pope in Pisa in 1409 and lasted until 1417.

Disease, war, and the loss of a single, sovereign spiritual leader promoted a climate of fear about the end of time. Normally in the role of the Vicar of Christ, in some circles popes became apparently associated with the Antichrist. While it is hardly surprising that the production of apocalyptic prophecy like the one above peaked in the last decades of the century, traces of this zeitgeist can also be discerned in contemporary polyphonic music. The ‘media hype’ around the papacy in the schismatic period is attested to by the emergence of compositions which specifically refer to popes in their poetic texts. Of some thirty surviving pieces, two allude to the fera ultima, and they do so to varying ends.

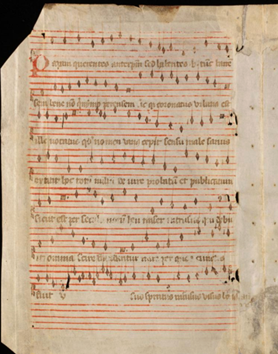

condemning pope Urban VI as the Antichrist. Universitätsbibliothek Basel, Fragment F IX 71. Image accessible here

The anonymous Latin motet Papam querentes / Gaudeat et exultet, composed shortly after the outbreak of the schism, mentions both the Roman pope, Urban VI (1378–1389), and his opponent, the Avignon pope Clement VII (1378–1394). Each of the motet’s two upper parts lends its voice to one of the popes. In the first voice (triplum), Urban is not only condemned as having been elected against the law (‘it is evident that this has been approved and published by no right’) but is depicted as causing the end of time, as the Antichrist himself (‘Searching for a pope but having an Antichrist…’). In contrast, the second voice (motetus) honours Clement as the ‘righteous priest’ about whose election the world should ‘rejoice and exult’

The association of the Antichrist, the fera ultima, with Urban VI coincides with the attribution of the above-mentioned papal prophecy to Urban. That Clement is shown in such a favourable light, moreover, reflects the use of prophecy as propagandistic tool predominantly on the Avignon side of the schism: among several dozen copies of this prophecy, only one refers to pope Clement as Antichrist.

This support for the Avignon papacy, in turn, is also corroborated by the overall corpus of papal music: four extant compositions honour Clement while no music connected to any of the Roman popes survives. In short, drawing on the evidence in eschatology and music, the historian might now ask how this one-sided picture in favour of Avignon came to pass: were the Roman popes not in need of such propaganda? Did they pursue other strategies? The research goes on.

The two-voice ballade Angelorum psalat tripudium by the very language of its poetic text––Latin––belongs to a very distinct group of pieces: of some four-hundred chansons which survive from the fourteenth century, only ten have a Latin (instead of a French) text. In addition to their papal texts, these ten pieces are inherently marked as mouthpieces of the papal curia by using the official language of the curia, Latin. This impression is further enforced by the fact that the manuscripts in which this repertory is preserved were likely compiled in the papal orbit

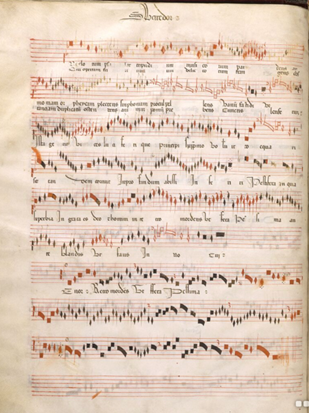

Our ballade’s initially joyful upper-voice text, Angelorum psalat tripudium (‘the rejoicing of the angels sounds to the cithara’), quickly proceeds to depict the fallen angel, Lucifer, ‘who wished to be the first leader’. The poem ends by describing Lucifer as ‘biting backwards like an evil beast’: retro mordens ut fera pessima. This poetic phrase is also reiterated in the ballade’s lower (tenor) voice, and it obviously plays on the apocalyptic subject. We cannot say with certainty which pope might be compared here with Lucifer, although patterns of manuscript transmission suggest that this piece was composed in Avignon or Pisan circles shortly after 1400: is this, again, propaganda against the Roman popes? In any case, the schism was not to be resolved until 1417 and so it is possible that the picture of an apocalyptical beast referred to yet another pope.

Musical compositions were much more than sung vehicles of clever textual references. Often preserved in luxury manuscripts, their compositional style, and the way they were written down—their mise en page—were an integral part of their overall message. Angelorum psalat tripudium is full of multi-layered information, since many things in this piece seem to happen ‘backwards’, just like the bite of the fera pessima. First, the relationship between red and black notation (reflecting the proportion between different note values) is reversed: in order to perform the piece correctly, one must read black notes as red and red notes as black. Second, the roles of the upper voice and tenor are reversed, such that the typically lowest voice (tenor) no longer provides the structural foundation for the composition’s upper voices. Here, the meaning of the complex tenor structure and the correct execution of its notation must be deduced from the metrical organisation of the upper voice.

In general, the extensive use of different note shapes and red notation in Angelorum psalat tripudium presents the reader/singer with every intricacy of musical notation that this period had to offer. Certain note shapes are even unique to this composition: the ‘virgulated semibreves caudatae’, as they are termed by scholars, might with their little ‘hooks’ (virgae) even remind us of the teeth of an evil beast. Finally, and amusingly, the name of the composer given in the top margin of the page (S. Uciredor), must be read in retrograde as well. It seems like this unknown ‘Rodericus’ was particularly keen on challenging the singer, reader, and listener of his musical composition. After all, the sheer amount of witty constraints his piece places on the performer may have served to conceal the fact that a pope is being compared to Lucifer himself.

In sum, music in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries made extensive use of its unique quality of being a visual and sounding object. Its origin in vibrant, courtly, expert environments caused a cross-fertilisation with other literary genres, such as prophecy, and cumulated in a multispectral reflection of current issues in society. Threatened with a multitude of existential crises, late-medieval society seemingly considered it acceptable to equal a pope with the Antichrist. However, although the presence of these musical and literary sources strongly suggests a propagandistic handling of societal concerns, the concrete contexts and actors—the poets, composers, and singers—remain shadowy: despite the undeniably enormous power of the (written) media, it is not always easy to determine who ‘wanted to bring water to their own mill’.

Johanna-Pauline Thöne, Doctoral Research Fellow, University of Oslo

Email: j.p.thone@imv.uio.no

Website: https://www.hf.uio.no/imv/english/people/aca/temporary/johannpt/index.html

About the Author

Johanna Thöne is a PhD candidate in musicology at the University of Oslo. Having a background in historical performance practice (harpsichord), classical philology, and musicology, she specialises in polyphony of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Her doctoral project investigates the cultivation of polyphonic music in the time of the Great Western Schism (1378–1417), in particular compositions associated with the multiple papal courts of that period. In addition to close analyses of musical compositions and manuscript transmissions, this project draws on an interdisciplinary approach rooted in history, philology, and literary studies. If anyone is interested in reaching out, please contact j.p.thone@imv.uio.no.

Bibliography

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate. 2006. Poets, Saints, and Visionaries of the Great Schism, 1378–1417. Pennsylvania.

Millet, Hélène. 2004. Les successeurs du pape aux ours. Histoire d’un livre prophétique médiéval illustré. Turnhout.

Plumley, Yolanda and Anne Stone eds. 2009. A late Medieval Songbook and its Context: New Perspectives on the Chantilly Codex (Bibliothèque du Château de Chantilly, Ms. 564). Turnhout.

———. 2008. Codex Chantilly: Bibliothèque du Château de Chantilly, Ms. 564: Introduction. Turnhout.

Rollo-Koster, Joëlle. 2022. The Great Western Schism, 1378–1417. Cambridge.

Verdú, Daniel (2023, February 6). Pope Francis says death of Benedict XVI was instrumentalized. EL PAÍS English Edition. https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-02-06/pope-francis-says-death-of-benedict-xvi-was-instrumentalized.html (acc. 10 February 2023).

Young, Crawford. 2008. “Antiphon of the Angels: Angelorum psalat tripudium.” Recercare 20/1: 5–23.

Links to the images:

https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/mirador/index.php?manifest=https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/iiif/374/manifest