Exploring Poulenc’s Paris and the Bibliothèque national de France

Kerry Bunkhall

At long last in June 2022, I embarked upon my first archival visit to Paris for my doctoral research, visiting the Bibliothèque musée de l’opéra and Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) at its Richelieu site. After two previous visits were thwarted by COVID-19, including testing positive the morning of my flight, it was a joy finally to be able to examine key documentation for my thesis and explore Paris through the lens of the research that I have so far undertaken.

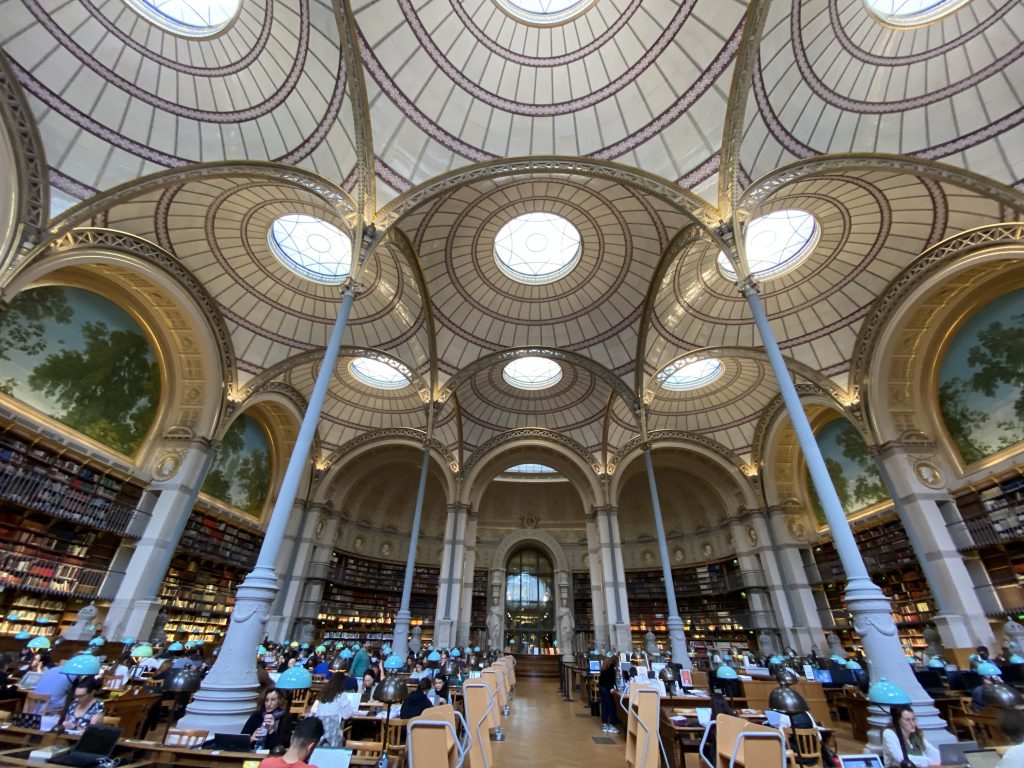

Being an academic twitter follower, I have seen many comments about the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of archival research yet still felt relatively blind walking into such grand and imposing buildings (as illustrated in Figures 1-3 below) without knowing where to go, what the protocol might be or how to approach the musical artefacts. With this in mind, I decided that I would share my experiences in this blog in case it may be helpful to other postgraduate students who may be feeling the same trepidation, along with an account of my time exploring some of the musical sites of Paris.

Fig 1. Palais Garnier, the home of the Bibliothèque musée de l’opéra and Opéra national de Paris.

Fig. 2. The Salle Labrouste at the Richelieu site of the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

Fig. 3 Manuscripts Reading Room at the Richelieu site of the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, the new home of the Music department.

Currently in my second year of doctoral research at Cardiff University, my project entitled Blanche and Dialogues des Carmélites: Martyrs for Poulenc’s Sins? explores potential motivations for Francis Poulenc’s re-embracing of his Catholic faith. It considers the context of nouvelle théologie, a religious ideology which was initiated due to great concern over the disconnect between faith and day-to-day life and which bridged the gap between the Church and Modernism. My thesis proposes Dialogues des Carmélites (1956) as the primary vehicle for Poulenc’s quest for redemption and absolution with the recurrent themes of guilt and the fear of death alongside the autobiographical character of Blanche de la Force.

Poulenc identified parallels between himself and the opera’s protagonist, Blanche, such as her overwhelming fear of death and suffering and her use of the Church as a form of sanctuary and security. Thus, I ventured to Paris to see the original manuscript of Dialogues, Poulenc’s annotated scores, programmes, press cuttings and a vast collection of additional fascinating documentation and photographs. As my thesis involves gaining a deeper understanding of Poulenc’s faith and potential sources of guilt, my hope is that these materials will provide clues to make informed analyses of Poulenc’s state of mind and help dissect his compositional approach.

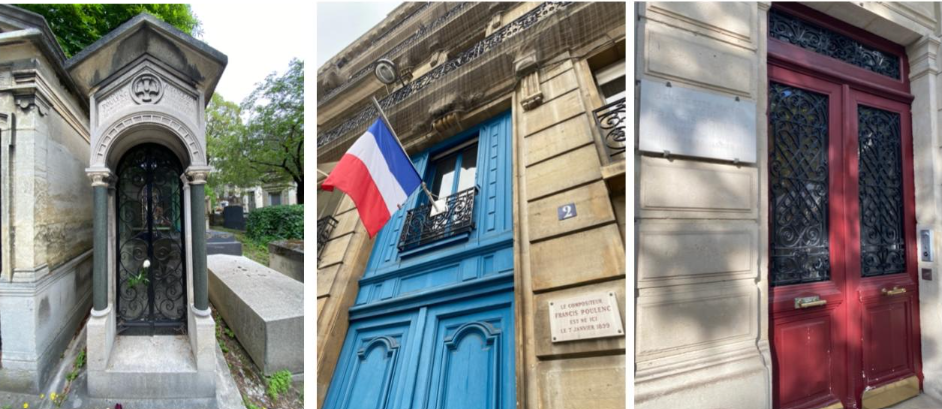

Before considering how I might have done things differently in my library work, I cannot stress enough how useful it was to walk in the steps of Francis Poulenc and see something of his Paris as preparation for delving into his archives. Being in Paris brought everything to life. I have been researching the Parisian artistic milieu of the interwar years for some time now and considering the ways in which different intellectual and creative spheres interacted. Being able to stand in front of prominent buildings in person, rather than just looking at a warped view on Google Maps, was not only fascinating but also helped me understand the creative network of Paris worked and how physically close so many great artists and venues actually were. When the library was closed, I visited Père Lachaise cemetery where so many of the great historical figures of Parisian artistic life were laid to rest, including Edith Piaf,

Sarah Bernhardt, Isadora Duncan, Apollinaire, Colette, Proust, Chopin and, most importantly for me, Poulenc himself. Similarly, I ensured that I visited Poulenc’s birthplace, where he went to church, the bars that he frequented and the apartment opposite the Jardin de Luxembourg where he departed this world in January 1963.

Fig 4-6: Left to Right: Poulenc’s grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery, 20th arrondissement; Poulenc’s birthplace at 2 Place des Saussaies, 8th arrondissement; Poulenc’s apartment at 5 Rue de Médicis, 6th arrondissement, at which he lived from 1947 and where he died in 1963.

During my travels around Paris, I was saddened that so many prestigious and historic venues were not only no longer operational but had vanished without a trace, devoid of a plaque or acknowledgement. For example, 28 rue Boissy d’Anglas in the 8th arrondissement once held renowned jazz bar Le Bœuf sur le Toit and the Magic-City amusement park by Pont de l’Alma in the 7th arrondissement was host to spectacular drag balls and held great importance to the homosexual subculture of Paris but now is merely a traffic intersection known as the Place de la Résistance. I could not help but remember photographs and videos of the frivolity and immense joy that took place in famous art deco bars and salons, which once held literary, artistic and musical greats, and feel a sense of loss as they have since been turned into shops or flats.

It is also sometimes difficult to retrace locations as streets throughout Paris have changed names since the interwar years. Nigel Simeone’s wonderfully informative Paris – A Musical Gazetteer (Yale, 2000) was a key source for notable addresses, making it possible to create an itinerary for a musical tour of Paris. His book offers great insight into the musical life of the city and provides vital context to the buildings that one will encounter. Another very useful source was Caroline Rae’s online Interactive Musical Map of Paris. All this did make me consider how important it is to know about the history of locations related to one’s research and how comparatively little I know of the history of the towns that have been significant in my own life; having walked around Bristol, Cardiff and London countless times. I’ve been ignorant of their stories and the roles that they played in establishing the culture that we have now.

In addition to exploring Poulenc’s Paris, the archive materials available to me gave a valuable and intimate insight into Poulenc as a man, as well as Poulenc the composer. The BnF preserves Poulenc’s own photo albums, allowing me to create a source listing everyone in his pictures and who he socialised with and where, alongside seeing him in a personal setting outside of his music, on a beach or playing with his beloved dog Mickey. However, the most meaningful moment for me was being able to hold the original drafts of Poulenc’s choral work Litanies à la Vierge noire (1936), a seminal work that marked a change in his musical and personal direction. Seeing his handwriting (as illegible as it may be) and the different inks and pencil markings showing his edits gave me an insight into his compositional process.

Stepping into the grand Parisian institutions of the Palais Garnier and Bibliothèque nationale for the first time is a daunting moment that brings with it a surge of inadequacy for a postgraduate research student overwhelmed by the sense of history that they represent. But, one has to take courage in both hands, draw a deep breath and remember that everyone has had to start somewhere! Nervous and unfamiliar with imagined protocols, I felt very much like a child wearing their mother’s high heels and, feeling rather an amateur in asking for assistance, I was almost afraid they wouldn’t consider me worthy to be in such prestigious establishments. But, my concerns were unfounded – the librarians were remarkably nice and very helpful. Something that is important to clarify is the set-up of the BnF as it is spread across multiple sites, all housing specific materials.

I was initially caught out by assuming that the music and opera departments were one and the same, whereas they work independently of each other and cover different aspects of Paris’ musical life. It is important to study the website carefully to see where you need to go, otherwise directly ask the librarian which address you will be required to attend to save confusion and valuable time.

The reading room at the Bibliothèque musée de l’opéra is blessed with its own grandeur, featuring several desks seated under a rather impressive chandelier. The computers are set to one side, offering a certain privacy and relief from the gaze of other researchers. The staff were incredibly accommodating, being willing to pull documents with only a few days notice at times. Reserving documents in advance is recommended, not only to ensure that the document is available and to avoid disappointment, but to provide you with a structure and starting point for your research.

It is best to assume that you will need to refer to all of the materials that you access in the future, carefully noting the reference numbers and any additional reference information that the file includes. It may be easy to source a page number of a book a year down the line but returning to Paris to simply confirm one reference would be quite an expensive inconvenience. One unexpected aspect was that reading rooms and materials can only be booked a month in advance which caused me great concern as I wanted to book my visit much earlier and was anxious that it may not be available. However, this was not an issue and everything was provided as expected.

For those who will be embarking on their own research in a library or archives, I would like to offer you my thoughts about certain practicalities to help you to plan your own visits, know what to expect and minimise the elements of the unknown. Although the list below refers specifically to my experiences at the BnF, the fundamentals can apply to working in any archive.

· First of all, speak to your supervisor; as an expert in your field they will likely know about the technicalities of the archives that you are visiting, and can point you to helpful resources or staff members there.

· Contact the librarians/archivists in advance or book documents that you would like to view online. In your preliminary email, ensure that you provide a brief description of your research, as archivists will often be able to suggest resources for you that you may not have been aware of.

· Find out in advance if the archive or library you intend to visit requires the use of Readers’ Card, or something similar, and how you can obtain this. In the case of some archives, you can apply online and simply collect it on arrival. For others, there will be forms to complete on arrival at reception.

· Ensure that you check online or with a member of staff what documentation or evidence is required for your Reader’s Card (or equivalent) as some, for example, the British Library, require proof of identification. Also, take your student card with you to evidence your status and ensure that you are charged at the appropriate rate.

· Decide how you are going to organise your findings. I find Excel the most beneficial option, as having columns for each of the pieces of information that I need to collect reminds me to document important data, such as the reference of the file, page number, etc. Being able to photograph the documents is a life-saver but, if you are like me, this can result in copious amounts of photographs that require storing and renaming. By deciding how you are going to do this in advance, you can save yourself valuable time and focus on the documents on the day.

· Photography is only allowed in certain archives and, if it is, photographs are ordinarily for personal use only. In some archives, getting a reproduction of a document will require payment and can be discussed prior to your visit, allowing you to simply collect on arrival. As with most things, it is important to research what is permitted in advance as it may change the scope of your visit.

· When you are arranging your visit, be conscious of the fact that many places will not allow large luggage due to security or space considerations so you will need to find somewhere to store it.

· Make sure you check out the opening times in advance as many libraries are closed on Sundays or may be closed for maintenance, moving etc. For example, accessing the Département de musique this year has been very problematic due to the closure of its premises on rue Louvois and relocation of the collections to the main building of the Bibiothèque nationale on rue Richelieu which is currently closed from June to September 2022. This would cause significant problems if you were to arrive without knowing! Also beware of falling foul of the Bibliotheque nationale’s ‘fermeture annuelle’ (annual closure) in September when the whole institution is closed.

What to expect when you arrive:

· Collect your Reader’s Card (or equivalent) and complete the necessary forms as required. Do not be afraid to ask the staff where to go and what to do as they will be used to people visiting for their first time and are generally very helpful.

· You will be directed to a locker where you can deposit your personal items. In most cases, you will only be able to take a pencil, paper and laptop or iPad that you may need into the library itself. Some lockers require a €1 coin so it is best to take one in case.

· You are then allocated a seat and your documents will be provided for you. In my case, the vast majority of the documents had been digitised to protect the originals and could only be accessed by using the on-site computers.

When researching outside the UK, there are multiple smaller factors to take into consideration:

· Ensure that you always bring a plug converter to the archives with you in addition to your laptop – a mistake I made in forgetting to do this on my first day.

· As the UK is no longer in the EU, using your phone abroad can cost a small fortune if not set up in advance so I would highly recommend contacting your provider before leaving to check up on data usage permitted.

· Do not assume that you will have access to the internet in the archives. The Bibliothèque de musée de l’Opéra did not have their own Wi-Fi, meaning that I had to use my phone as a hotspot and this would have cost me a pretty penny had I not arranged a roaming package with my provider in advance.

· When using an onsite computer, be aware that the keyboard arrangement may not be what you think! I had forgotten that computer keyboards in France have a very different ‘azerty’ arrangement and can therefore be tricky for those used to the standard ‘qwerty’ format.

One aspect that I had been acutely aware of, but underestimated, was the deathly silence of a proper research library where one hears only the delicate turning of a page. I was utterly terrified of dropping something, as is my usual practice! As someone who has music, a podcast or the television blaring on all occasions, sometimes simultaneously, I found the startling silence both useful to focus my attention and at times rather intimidating. The wondrous silence almost felt like a connection to others in the room who were similarly focusing intently on their research; this helped me to dedicate all my faculties to the documents in front of me. Although it may seem to add tension to the room, the silence can become your ally and a change in perspective can turn it around from being intimidating to motivating.

My final piece of advice is to recognise yourself as a scholar approaching high-level research and dedicating your time to your own area of expertise. Rather than focusing on one’s relative lack of experience, remind yourself that you have been granted access to these documents for a reason and that, if you intend to pursue research, whether through academia or an alternative route, this will be a part of your life rather than a one-off experience. For me, the revelation that visiting archives and accessing historic artifacts could be the norm reminded me why I was dedicating my time and efforts to my doctorate. The whole experience is very exciting!

Finally, plan you research before you go but be aware that once you’re there you will also find unexpected treasures.

Kerry Bunkhall 2nd Year PhD Candidate, Cardiff University

Email: bunkhallks@cardiff.ac.uk

Twitter: @kerrybunkhall

A fantastic read, thank you Kerry. Really insightful and considered, I know that this blog will help me in my own research and in planning research trips to Europe.