Alan Bush’s 70th birthday concert in Apartheid South Africa

In this post, Dominic Daula gives us a fascinating insight into the influence and legacy of British composer Alan Bush in South Africa. Dominic is currently a postgraduate student at the Royal Northern College of Music, having previously studied at the University of Cape Town.

Profile

Alan Dudley Bush (1900-1995), a composer regarded by some during his lifetime as the enfant terrible of his professional circle in Great Britain, is undergoing a period of critical reassessment in the twenty-odd years since his death. The narrative which surrounds Bush’s personal and creative personality remains a complex topic and some of the discourse in need of reassessment recycles arguments which present the composer as either a victim—either at the hand of his opponents within the Establishment for being a public supporter of Communist and anti-imperial sentiments; or a victim of artistic neglect, that his music was considered by some quarters as tonally regressive. He may, in my opinion, be a victim of his own cause as a result of not heeding the discontent expressed by his colleagues and cultural authorities in the first two scenarios of victimhood I mention as present in the extant literature on the composer.

Bush’s Connection to South Africa

As professor of composition and harmony at the Royal Academy of Music, Bush enjoyed an unusually long tenure—first occupying this position in 1925 and retiring in 1978, with two comparatively brief sabbaticals (for further studies in Berlin and military service respectively). The Academy,an institution of consequence in the United Kingdom, was of even greater prestige to musicians of other countries, particularly those influenced greatly by British culture or that fell under its colonial agenda.

Bush, who witnessed the territorial repatriation of the former Empire (probably to his pleasure, given his contempt toward imperial ideologies), was one of many British musicians who educated the stream of South African students at various stages of their professional development. Notable South African students who benefited from Bush’s tutelage in the 1950s and 1960s include Hubert du Plessis , James May, and Carl van Wyk. All three distinguished themselves as prize winners within the institution and unanimously admired their teacher. In particular, James May began an extensive and endearing correspondence with his former teacher from the end of his studies till 1976,[1] supplemented by personal visits on an annual basis to Bush’s home in Hertfordshire until 1983.[2]

The correspondence between Bush and May serves as a primary source of much relevance to this essay, as it illustrates the desire of both to raise the creative position of one another. May goes about this by bringing the work of his teacher to the attention of music practitioners and enthusiasts in South Africa by means of performances (such as the concert which forms the broad subject of this essay) and radio broadcasts.[3] Bush, who considered his student to be a ‘sensitive and artistic composer, [with] a subtle ear’,[4] used his professional position and influence by introducing May to musicians resident in Britain in an effort to secure concert performances for him in venues outside of the Academy. When May grew more disillusioned with his compositional path and decided to pursue a musicological career, Bush acted as a referee in support of May’s successful application to a lectureship at the University of Cape Town. The concert which May organised a year into his appointment can certainly be considered a gesture of gratitude to his former teacher.

Though Bush never visited South Africa, its music and then contemporary political situation occupies a fair amount of programmatic representation in his output. A great ally of the liberation movement throughout the (African) continent, Bush was admitted as an Honorary Member of the African National Congress. His portfolio of compositions which recognise South Africa do so by highlighting (to the best of his ability) certain aspects and systematic procedures proper to South Africa’s Diverse musical traditions. However, the interethnic musical process is executed in ways which can be considered simplistic or naïve, as in the Three African Sketches, opus 55 (1960) for flute and piano, his earliest work in this musico-geographical vein, which seems to follow a Bartokian approach, illustrated in the way which the original pitch material undergoes a process of formalisation when adapted to a Western idiom, losing much of the organic characteristics proper to the more foreign musical practice.

In later works such as Africa, opus 73 (1972) for Piano and Orchestra and in Mandela Speaking, opus 110 (1985) for Baritone, Mixed Chorus and Orchestra, Bush widens his compositional objectives by simultaneously celebrating the musical heritage of the region, appended by an explicit political statement highlighting his condemnation of the totalitarian government’s formalised policies on the disenfranchisement of its non-white population.

Why then, would Bush permit for his music to be performed in a country he is at odds with from a political standpoint? Though non-white audiences were permitted to attend concerts on University property, it is unlikely that news of this event would have reached them. Did Bush perhaps hope that his notoriety as a communist (a principle which irritated many of the apartheid apologists) would have spread to South Africa, thereby attracting a concert demographic of liberal minds? Or was Bush’s condemnation of South Africa’s political policies put on hold for his own careerist aspirations?

To provide some nuance around these questions, I should mention that the works which carry an anti-apartheid programme were completed in the years following the concert in Cape Town, starting with Africa, a significant symphonic movement for Piano and Orchestra which chronicles the struggle against oppression in South Africa, with a musical depiction of the Sharpeville massacre of 1961, an incident which was met with disapproval from the international community. The work ends with a musical depiction of a peaceful and liberated South Africa which, considering that the regime was in effect for another twenty years, must have been regarded by the disillusioned as an unrealistic pipe dream. The composition has never been performed in South Africa but enjoyed a number of performances and broadcasts in Britain and continental Europe. A work which managed to communicate Bush’s political activism against the apartheid government is the anthem Africa is my name, opus 85 (1976), which combines music set to a text by Nancy Bush (the composer’s wife) with the anthem of the African National Congress. The ANC as well as its anthem (which was adopted by other African countries in their campaigns for independence) was banned by the apartheid government, which highlights a progressive element in Bush’s political conscience.

Birthday concert in Cape Town – 30 April 1971

This concert marked the first extensive presentation of Bush’s solo, vocal, and chamber music in South Africa,[5] and such a tribute concert of contemporary music in the university’s concert series was preceded by one in the previous year (also curated by James May) dedicated to the piano music of the Second Viennese School.[6] Like Bush’s music, the repertory of the Second Viennese School was hardly performed in South Africa, though in Bush’s case the dearth in performances was due to a lack of access to his published music rather than the well-established stylistic infamy of Schoenberg and his followers.

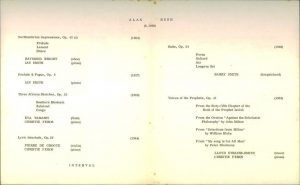

The programme was well curated in that it covered, through six works, a comprehensive overview of the composer’s oeuvre together with a nod to the defining features of his stylistic idiom at various parts of his professional career. The programme includes his Prelude and Fugue, opus 9 (1927) for piano, which dates from the early part of his career, during which his works embraced the characteristics proper to musical expressionism coupled with a sophisticated and chromatic harmonic language. Also in the programme are works of nationalist sentiments, such as the Northumbrian Impressions (opus 42a), and the Suite for Harpsichord (opus 54). The nationalist programme is further explored through his interest in the workings of music proper to other cultures, as evidenced in the Three African Sketches (opus 55).

The final work on the programme, titled Voices of the Prophets (opus 41) is a cantata of four songs for tenor and piano. It is a composition of particular significance in Bush’s output, as a work which distils Bush’s compositional idiom and personal philosophies. John Ireland (Bush’s composition teacher in the 1920s) opined that Bush had ‘found himself’[7] as a composer in this cantata, thereby supporting my observations of the work’s significance in his oeuvre to that date.

The cantata provides a sense of stylistic unity in the concert programme, as it contains traits of Bush’s musical personality at various parts of his career. The first two songs are written in an idiom of polyphonic rigour, in which the first employs stile antico compositional techniques. The second explores florid counterpoint and celebrates the composer’s virtuosic abilities as a pianist. The third and fourth songs expand on the virtuosic potential of both singer and pianist, and places greater emphasis on rhythm as a contrapuntal property rather than pitch material. The intense polyphonic qualities that these songs contain is a nod to his early training as a composer during which he studied counterpoint in the style of Palestrina. Every significant work in Bush’s compositional career was written in a contrapuntal vein, and it is the enduring stylistic feature of his idiom.

The texts which Bush set in this work reflects his interests in the utopian and ideological (Isaiah, Milton, Blake) and his proclivity to propagate messages against divisive and socially unjust policies that exist in the world (Peter Blackman). In this sense, Voices of the Prophets ultimately marries Bush’s progressive attitudes of social consciousness with his intellectual nature which is broadly reflected by his interests in philosophy, and from a musical standpoint, the contrapuntal rigour and careful pitch organisation which constitute his idiom.

This concert took place some weeks after the Royal Academy of Music celebrated Bush’s seventieth birthday with a musical event of their own, [8] though its programme was unbalanced and mainly consisted of piano music, two songs from Voices of the Prophets, and one instrumental work (the Concert Suite for cello and piano, opus 17) albeit a significant one. The Cape Town concert programme was constructed with partial involvement from the composer, who understood the professional benefits it could provide him, remarking:

I am not very publicity conscious, but such a concert as this so far away from Britain is quite an event and it might impress some people with the idea that some of my works should be played more often than once every ten years.[9]

Epilogue

The concert was met with some favourable attention, garnering an article in the local press. More significant was fan mail which Bush received from Walter Swanson, a musical pedagogue who wrote most favourably about the event. To Bush’s pleasure, he also revealed that he had staged one of his children’s operas at his workplace, which was an educational institution for Coloured Teachers. In a letter of gratitude, Bush wrote to James May on the feedback he received from Swanson, and commented:

I must say that looking at it like this, there is no doubt that it was one of the most comprehensive programmes of my works which has ever been given. Swanson spoke particularly of the splendid performance of VOICES OF THE PROPHETS.[10]

What could be interpreted as a gesture of gratitude to his former teacher was met with a reciprocity of appreciation. Bush, whose letters to his former student had for years maintained the dynamic of master and apprentice, lowered his guard and began to treat May as a colleague, signing off his letters as ‘Alan’ dating from 10 May of that year. However, May found this difficult, and continued to address Bush in formal terms, resulting in a curt postscript note almost three years later which read ‘Please drop the Mr Bush. We are both grown up men’.[11]

Acknowledgements

Emeritus Professor James May for granting me permission to make use of his correspondence with Alan Bush for research purposes.

Santie de Jongh of DOMUS (Documentation Centre for Music) at Stellenbosch University for providing me with a copy of the Hiddingh Hall concert programme dated 30 April 1971.

Notes

[1] This refers to extant correspondence which was in the personal possession of Professor May at the time he donated copies of the letters to me for research purposes in 2016. At the time of donation, the file of correspondence contained several lacunae.

[2] James May, interview with Dominic Daula, 1 February 2016.

[3] Alan Bush, letter to James May, 7 May 1971.

[4] Alan Bush, reference letter for James May, 16 December 1965.

[5] The concert was initially projected to take place on 13 November 1970, as evidenced in a letter from AB to JM on 23 August.

[6] J Brooks Spector, “South Africa’s Special Songs.” Daily Maverick. 3 July 2017, accessed 17 June 2018, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-07-03-south-africas-special-songs/#.Wyg2d6dKjIU

[7] John Ireland, letter to Alan Bush, 8 November 1953.

[8] Alan Bush, letter to James May, 20 October 1970.

[9] Alan Bush, letter to James May, 29 April 1971.

[10] Alan Bush, letter to James May, 7 May 1971. Bush’s capitals.

[11] Alan Bush, letter to James May, 14 March 1974.